Blogs in the world of medical education are taking off and seem to be serving a number of unique purposes. I blog in an effort to turn the scattered ideas that are racing through my mind into relatively coherent summaries of information (you be the judge). Publishing these summaries allows me to get feedback on my thinking from readers. I blog to process and learn.

Blogs can also be resources. An idea has been tossed out by the awesome folks at the USask FOAM Collaborative to start bringing together and building a repository of FOAM. This would be a site managed by Canadian medical students/residents for Canadian medical students/residents (and anybody else who desires amazing content organized around the Canadian curriculum). This sort of blog would be a common resource for learners across the country because it is built on the foundational curriculum that we all learn from (MCC Presentations or residency equivalent). This type of site, though associated with learning goals for the creators, would also have huge benefits for the target audience. It would serve as a flexible FOAM curriculum of sorts. With some ironing out of the idea and a lot of elbow grease, this blog will be a great resource.

A number of medical educators blog including the Queen’s undergraduate medical education team. Most posts come from undergraduate Dean Tony Sanfillipo and/or educational developer Sheila Pinchin. Check out the Queen’s UGME blog that covers everything from teaching tips, to the hidden curriculum, to debates about admissions strategies. This blog is primarily about medical education and directed towards teachers.

So…after a lot of thinking and a bit of discussion with some fellow social media enthusiasts and even a few skeptics, I think it would be pretty awesome and maybe even feasible to build a blog that does all three. A blog by medical students for processing and learning that serves as a resource for other medical students but that is simultaneously directed at medical educators. There are some really great medical student blogs that bring these three together naturally (ahem Lauren Westafer at The Short Coat) but it would be neat to get the perspectives from a number of students in the same program.

So, what would that look like?

__________________________________

Create a class blog focused on documenting and evaluating specific learning moments throughout clerkship. It would serve as a mechanism for medical students to learn through each others’ experiences to inform learning. This resource would also be a unique way for faculty members and medical educators to better understand how medical students experience clerkship and what learning experiences they find most effective. A blog that is updated and managed by students would further our development as physicians who are collaborators, communicators, medical experts, advocates, scholars, managers and professionals.

The ask would be simple:

In 250-1000 words submit an entry for the Clerkship Blog. In your entry please describe:

- Something you learned: this can be about anything including medical concepts, techniques, communication skills, about advocating for a patient, a personal reflection etc.

- How you learned it: explain who was involved in the learning process and what the learning experience was. For example, a resident, attending or patient taught you; you read about it in a textbook; through simulation; trial and error.

- What you would change: if you could learn this task or lesson again, what would you do differently?

Coordination

- Recruit 4-6 volunteers who commit to submitting posts once every four weeks in a rotating fashion. This will ensure that the blog is updated frequently and these posts can serve as model entries for peers.

- Ten students per block (every 6 weeks) will submit a post according to a predetermined schedule. Students are also welcome to contribute additional posts if they so choose.

- Submissions can be posted with names or anonymously.

- Student leads would be responsible for collecting and posting submissions to the blog.

- Student leads will screen posts for issues related to confidentiality and professionalism.

- Students submitting posts with professionalism concerns must revise entries before they are posted. A faculty member could advise this process as needed.

- Student leads will screen posts for issues related to confidentiality and professionalism.

Objectives

- Develop a unique learning environment for clerkship students to document learning experiences

- Create a repository of learning methods for students and faculty

- Foster a sense of community

- Build a model of professionalism skills related to social media

______________________________________

So, do you think this type of blog or something like it could be a triple threat? Would it help students process and learn, serve as a resource for peers and inform medical education?

Today I learned the term straw dog (yes this that is referenced to urban dictionary) or straw man proposal. It is an idea or plan put forth only to be knocked down with the hope that the critic puts forth an even better idea. This is my straw dog of the day. Any feedback, suggestions, criticisms, thoughts or other cerebral processes about this idea are welcomed and encouraged. This is a work in progress and could seriously benefit from some further shaping by medical students, medical educators and the #FOAMed/#meded communities.

Yesterday our class wrote the gastroenterology exam, which means another term of medical school down and one more to go before clerkship. For this exam we studied hard and were prepared for the inevitable questions that came up about cholestasis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, colon cancer and everything else feces and flatus related.

What caught many of us off guard though was a question related to cyclic vomiting that is relieved by hot showers and the key historical feature of marijuana use. Instead of just letting it go, I thought I’d throw together a simple med-student review (using the illness script format from the Clinical Problem Solving Course) for cannabinoid hyperemesis, to prepare us for next time….especially because that next time will be with a patient, not an MCQ. The increasing medical use of marijuana and a high past-year use of marijuana rate (10% in Canada) make this a particularly relevant condition for medical students to understand.

Illness Script

Epidemiology: Cannabinoid hyperemesis typically presents in adolescents and young adults. The key risk factor is daily cannabis use over months to years, usually starting in the teenage years. Approximately 5% of grade 12 students use marijuana daily (US statistic but my guess this is a fairly good estimate of Canadian data), meaning that a big chunk of the population is at risk. Other patients at risk are those using marijuana daily for medical purposes.

Time Course: This is a chronically developing condition with a number of stages. In the prodromal phase patients have symptoms in the mornings and on 1 or 2 days of the week. In the active phase patients have disabling cyclic episodes that recur on a weekly or monthly basis for years.

Syndrome: The clinical syndrome of cannabinoid hyperemesis is well described in a recent review as profuse vomiting, intense sweating, colicky abdominal pain and compulsive hot bathing (multiple hot showers or baths for a mean of 5 hours daily).

Mechanism of Disease: The active compound in cannabis, THC, usually acts on the CB1 receptors in the brain to produce anti-emetic and psychoactive effects. The mechanism through which cannabis exerts paradoxical effects is unclear but is thought to be related to excessive or toxic levels of consumption also activating CB1 receptors in the gut. Activation of gut CB1 slows peristalsis and gastric emptying in a dose dependent manner. Meaning that with excessive intake, the nausea and vomiting associated with GI CB1 activation overpowers the anti-emetic effect of brain CB1 activation. The vomiting becomes cyclical because patients self-medicate with marijuana which leads to a worsening of symptoms and even more marijuana use. The compulsive need to take hot showers in these patients may also be explained by hypothermic effects associated with THC mediated changes in core body temperature. The idea that chronic marijuana intake could reach toxic levels, and what those toxic levels are is still up for debate! For some more details on the complex and emerging theory see here, here and here.

Using the Illness Script

The beauty of this illness script is that there are key features (history of chronic cannabis use and compulsive bathing) that distinguish it from other causes of cyclic vomiting (cyclic vomiting syndrome, drug withdrawal syndrome, bulimia, hyperemesis gravidarum, Addison’s disease and other metabolic conditions, psychogenic vomiting and migraine headaches). These key features are not complicated and can be obtained by taking a good history. Identifying the features of this syndrome in the absence of other causes cinches the diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment

A recent review of the the differential diagnosis, diagnosis and treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome can be found here. The take home message is that compulsive nausea and vomiting, relieved by hot showers in cannabis users of more than one year is pathognominic for the condition. Further medical testing may not be necessary and cessation of cannabis use and fluid replacement are the mainstays of treatment. Rarely cannabinoid hyperemesis can be so severe that it is associated with shock, metabolic disturbances and other complications (see this reported case) so just like any other patient that comes through the doors managing those ABC’s is important.

Morals of the Story

- Sometimes exams make you think…you can learn a lot by identifying what the tough questions were and spending a bit of time reading around them after you leave the test. For more on that see my previous thoughts on exams.

- Ask patients who are vomiting about marijuana use

- Ask patients who are vomiting if hot showers relieve the condition

- To avoid cannabinoid hyperemesis don’t use excessive amounts of pot daily for years

- To stop cannabinoid hyperemesis patients need to stop using which is much easier said than done. Helping patients get the help they need to do this might make a big difference.

Even Better FOAMed Resources on Cannabinoid Hyperemesis

- Life in the Fast Lane Q&A, case presentation and Grand Rounds

- The Poison Review

- Incision and Drainage Commentary

- Movin Meat

- EMRap Episode

- And two wild cases of pediatric cannabinoid hyperemesis

The injury trifecta of proximal fibula fracture, distal talofibular ligament rupture and torn anterior delta ligament (or avulsion) was first described by the French surgeon Jules Germain Francois Maisonneuve in 1840. This specific pattern of ankle fracture is now recognized as the Maisonneuve fracture. It is caused by external rotation of the foot relative to the tibia which causes rupture of medial ankle ligament leading to diastasis (separation of tibia and fibula) and energy transfer out of the fibula. The disruption of the syndesmotic ligaments and the interosseous membrane from the ankle all the way up to the level of the fibula fracture make it an unstable fracture. It is important to recognize but easy to miss….especially as a medical student.

The Case

An otherwise healthy 44 y/o male presents with R ankle pain and inability to weight-bear after falling off a horse. The exact mechanism of injury (external/internal rotation or pronation/supination) is unclear. R ankle is diffusely swollen with tenderness over the tip of the medial malleolus. Neurovascular intact. He has no other injuries.

The important historical fact that this man was thrown off a horse and positive screening with the Ottawa ankle rules (for which this patient doesn’t really qualify because of high impact mechanism of injury but increase my suspicion of fracture anyways) make me think that he needs an x-ray. I present to the attending with this plan. After discussing our fear of horses, she agrees and we order the ankle series. This is more or less what we get back.

A perfectly normal looking ankle…on x-ray at least. There is no way- I don’t believe it. I express my surprise at the negative x-ray given the patient’s presentation to the attending and she asks, “well did he have any proximal fibula tenderness?”. I had checked, and he did. So we order an AP proximal fibula. This is what we get next.

A spiral fracture of the proximal fibula. So now we are working with: medial malleolar tenderness, bruising and swelling and a fibula fracture. With the new knowledge in mind we review the original ankle films and are able to convince ourselves (maybe with a little confirmation bias) that the joint space might be a tiny bit wide. Nothing like some more impressive Maisonneuve’s that look like this:

We consult ortho and sure enough they agree. He is scheduled for follow up, and likely surgery (necessary for most Maisonneuve fractures) the next day. A discussion of the treatment is beyond the scope of this article but a nice review of evidence-based management of this injury can be found here.

So what about the Eponym?

This whole clinical encounter would have been much smoother if I had just known the eponym. At the time I didn’t know what a Maisonneuve fracture was. I knew enough to look for proximal fibula tenderness in my initial physical exam because I had remembered learning something about energy transfer through the interosseous membrane in ankle injuries, but I couldn’t put it all together. I didn’t know the words to describe what I was worried about. The word Maisonneuve would have really helped me express what I was thinking.

In the online Clinical Problem Solving course through Coursera we are learning about the importance of problem processing. The importance of taking a patient’s complaint and turning it into medical language that triggers our memory about the condition and that allows us to communicate efficiently. I know they are a hot subject but like it or not in this case and for many other conditions eponyms are an important part of problem processing.

Instead of sending the patient back and forth to x-ray and taking up time and space in a busy ED if I had said the first time, “I am worried about a Maisonneuve fracture” he could have had both x-rays at once. I am a fan of only ordering the necessary tests but this clinical situation (if I had been able to describe it appropriately to staff) would have warranted pictures of the ankle and the proximal fibula. A recent case series describes 5 patients who were evaluated in the ED then later found to have missed Maisonneuve fractures. The discussion suggests three reasons why Maisonneuve fractures are routinely missed:

1. You didn’t examine the proximal fibula. If patients complain of pain in the ankle and you only examine the ankle then you will not find proximal fibula tenderness even if it exists. Often the ankle pain is severe enough for patients not to recognize pain at the fracture site until you push on it. Any degree of tenderness should raise suspicion.

2. The lack of proximal fibula pain (because it wasn’t examined) will also mean that this sight is ignored radiographically as well. No pictures of the proximal fibula mean no fracture to diagnose.

3. Often the ankle x-ray is taken non-weight-bearing which increases the likelihood that it will appear normal. The stress of weight-bearing may widen the syndesmosis making the defect associated with the Maisonneuve more obvious. When the joint is unloaded articulations may recoil and the joint may look normal.

So…if you don’t palpate the proximal fibula and the ankle film looks normal (which it might) the patient could be discharged with an unstable ankle fracture.

Morals of the Story

- Palpate the fibula…x-ray if it is tender and given the right clinical scenario

- Learn eponyms unless there is better term to describe the process or injury. This will be hard because I am bad with names, let alone 100-year-old dead guy names.

- Mechanism of injury is everything in injury assessment. Knowing the mechanism allows you to employ a “forward thinking” approach to use the physical exam and appropriate x-rays to rule in and out specific fractures that are most likely given the injury pattern. As a medical student, knowing these mechanism-fracture pairings (which are a pain to memorize) might make you look like a rockstar one day when you use forward thinking instead of a shotgun approach to diagnose a fracture.

- Don’t ride horses

At Queen’s Medicine, Monday lunch means the Healthcare Management Interest Group meeting. Throughout the term students organize for physicians with double careers or special interest in business, politics, health policy or administration to speak with pre-clerks. We hear about impressive careers and about what medical students can do if we wish to build a strong foundation to pursue a similar path. We learn from those who in medical school were involved in student government through OMSA, CFMS and CAIR (in residency) or who pursued an MBA or who volunteered overseas. Each of these stories is inspiring. However, this week’s simple lesson from Dr. Ruth Wilson (who has an awe-inspiring, illustrious career of her own) made the most sense, came as a big relief and was an important reminder for me as I make my way through medical school.

So…what what was Dr. Wilson’s top tip for medical students who seek to make a difference in their careers? FIRST, BE A GOOD CLINICIAN. If you love what you do, if you are good at what you do and if you say ‘yes’ a few times along the way you are sure to build a career that serves patients and the profession well. It might also just make you happy too!

What is so relieving about this message? I often find there is pressure on and from medical students not just to excel in medical school but also pressure to be involved in many other domains along the way. Walking through the halls you will hear students speaking about their research, their volunteer activities, their healthcare management interest groups. I fully admit to being one of those students. This is not a bad thing, it just seems to be the reality of medical school. The CanMEDs roles on which our curriculum are founded, are seven key roles of the effective physician. We learn about the Medical Expert, the Communicator, the Collaborator, the Manager, the Advocate, the Scholar and the Professional. We learn about these roles then as diligent medical students work to embody them. Often this effort comes outside of our typical medical student domain. Often these commitments take up time, they sometimes stretch our schedules thin. Do I regret this peripheral involvement? Absolutely not. Will I continue to be involved? Absolutely- but I will do so now with a better understanding that it is perfectly okay not to be an expert in these areas, not yet at least. It is comforting to hear from the expert that it is perfectly reasonable not to have a 10-year plan if you have a willingness to work hard, enthusiasm to learn and desire to do good by those around you.

Though I won’t let Dr. Wilson’s humility fool me into believing that being a good clinician will be enough to set me up to make even close to as significant a difference as she has made, I do buy into the fact that it is the first thing I must do to even have a shot! Her advice came at the perfect time. As this semester winds down and the pre-clerks storm the New Medical Building for lockdown study mode we will try to remember that as a medical students: if you love what you do, if you are good at what you do and if you say ‘yes’ a few times along the way… the rest will follow.

In clinical skills we throw around the terms tracheal tug and intercostal indrawing. The number of times that I have said to a tutour or examiner, while evaluating a healthy patient, “I see no indrawing” or “there is no tracheal tug” is honestly a bit ridiculous. It is ridiculous because I had absolutely no idea what I was looking for.

So, when I examined a young patient in the ED with these findings I did not notice what I should have. When the attending asked about respiratory signs of distress, I mentioned the increased RR. He asked me about indrawing and tracheal tug and I replied, “no”, but with the important caveat that I had never actually seen these clinical signs in a patient. An important caveat, because when we then evaluated the patient together my teacher pointed out the rather remarkable and now obvious tracheal tug and intercostal indrawing. I can’t believe I missed it. Though I was sure that I had looked, all I had really done was go through my mental list that included “no indrawing”.

Now I know what these signs look like- watch the video below to find out.

Before this clinical encounter we had just finished our respiratory block. I could have easily described the physiology associated with indrawing and a tracheal tug. I could have talked about their clinical importance. I knew that I was supposed to look for them when I saw patients with respiratory complaints. But this encounter was a humbling reminder that the classroom isn’t the bedside. My book knowledge became irrelevant because I misevaluated the patient.

The moral of the story

- It may be helpful for students if teachers include more videos to demonstrate relevant clinical signs in classroom teaching instead of just explaining the concept or using pictures.

- Students need to be honest with themselves and teachers about what they know clinically and what they don’t. I don’t feel comfortable accurately commenting on something that I have never seen.

- Teachers need to question students’ negative findings! They may not be negative, we just don’t know how to see the positive.

- It is extraordinarily helpful when teachers take time to point out clinical findings no matter how simple they seem. To students they are new and foreign.

Last night over 200 medical students, residents and faculty gathered at a local pub for a good old fashioned game of trivia. We mixed and matched to form teams of all levels of training then faced off. Believe me, this type A crowd took it very seriously but despite ourselves we managed to have a bit of fun too. The great event got me thinking about the history of trivia and its interesting role in medicine.

Trivia -defined as unimportant matters, facts or details- originates from the latin word trivium meaning the meeting of three ways or crossroads. Historically, a tavern would exist at these intersections and in such establishments the sharing of ideas would take place. But we all know, the more beers behind an idea the better it seems and less important it usually is. On these grounds, intellectuals dismissed public house communications as insignificant and unimportant…to the intellects they were trivial.

Fast forward a few centuries to the 1400s and trivium takes on a new meaning as the group of three studies comprising the liberal arts: grammar, rhetoric and logic. Now, trivium is not seen as useless or insignificant in the eyes of the intellect but in the eyes of the commoner these subjects are entirely irrelevant. The peasant finds the art of discourse trivial when he is faced with the task of putting food on the table for his hungry family.

So what does this quick look at the history of trivia have to do with medicine? It reminds us of different perspectives. The intellect dismissed the tavern and the commoner dismissed scholarship. Both did so without first considering the other’s perspective. The intellect did not see the tavern for the opportunity of business and connection that it presented to the commoner and the commoner did not see scholarship as an opportunity for growth and progress in the way that the intellect could. Both were wrong.

So, as I continue to diligently pack what I perceive to be important knowledge into my brain (99% of which I imagine would be considered trivial to most) I will work to remember that I learned more sitting around a table at the Merchant with colleagues and mentors socializing over trivia then I did all day at school. I will try to remember this when I am seeking to understand my own perspective and the perspective of patients, attendings and peers. My hypothesis is that most disagreements will be explained easily by differences in what each party considers to be trivial.

For a short video on the history of trivia see this great video.

A new blog, a new resource, a whole new way to learn about Cardiology for medical students! Prof Montage: Cardiology Rounds is designed to help us explore cardiology topics (cardiac physiology, clinical cardiology and clinical epidemiology) through a series of short (<3 minute) animated videos!

In the first we are introduced to an entertaining cast of characters that can be found in any medical school class. They are the:

- rich kid doing a medical degree to secure his future

- nice alternative girl with strong ethical guidelines and moral boundaries

- “A” student who knows a lot of the material and asks only hard questions

- P=MD student who asks easy but important questions

- The jokester

- and Prof Montage the ward rounds doc and knower of all things cardiology

These characters appear in all videos providing the viewer with familiarity and a slightly pathetic attachment- a bit like your favourite sitcom character. I am a fan of the “jokester” who seems to bring comic relief to some otherwise serious learning.

When I was directed to this site today I fully intended to watch one video and move on but found myself saying “it’s only 3 minutes, I’ll watch one more.” At least this is more productive than my usual, “another episode of Modern Family…that’s only 20 minutes, I’ll watch one more.” In 30 minutes I was able to review coronary flow, preload/afterload/contractility, left ventricular hypertrophy, troponins, NSTEMI, aortic stenosis, aortic incompetence, epidemiology of major adverse cardiac events, absolute and relative risk and survival curves. All this while laughing out loud on a few occasions.

Improvements

My main complaint would have to be that the computerized voices take some getting used to. People might be quick to move on if they don’t like the audio. Improving the quality of the audio might make people more likely to watch a second, third or fourth.

To make the resource even better a cheat sheet on the take home messages from each topic would be awesome!

This week I am presenting at our medical student run journal club. Ours is a traditional gathering that meets every other week and is meant as an opportunity for students to develop critical appraisal skills. We usually explore articles that are relevant (or sometimes irrelevant but entertaining) to our learning.

I have participated in a few, and would like to engage with more, online journal clubs-a few of which include: #twitjc, #JC_StE, #PHTwitJC, #microtwjc, #urojc…

The most recent meeting of #twitjc was a discussion of the 2013 NEJM article- Transfusion Strategies for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding– and it just so happened that in class we have been learning about acute GI bleeding, with some emphasis on transfusion guidelines. The combination of a relevant paper, a great #twitjc discussion and my turn to present is the perfect storm. Tomorrow traditional journal club is going to meet its future-self, twitter journal club. It is something like Archie Cochrane meeting Mike Cadogan– this is going to be good.

So for now, wish me luck as I try to introduce the traditional journal club enthusiasts (of which there are relatively few in medical school to begin with) to the wonderful world of twitter-based discussion! The planned presentation is below. If you have any suggestions, I am all ears.

Wait…anatomically that doesn’t make any sense? Though I guess glucose does have to make it through your gut before your brain can use it as fuel!

Timbits, free pizza, fruit trays, snacks for small group learning, lunchtime sandwiches…This post is all about food and the relatively central role it seems to be playing in my medical education. “Food? Really?…central to medical education?” you might ask. Yes…it comes up a lot- just ask any medical student. I am not talking about learning diet counselling for patients (maybe something we should learn more about), I am talking about medical students’ consumption of food. Here are just a few examples of what I mean.

- When interest groups (extracurricular student-led groups that are focused on specific areas of medicine i.e. Family Medicine, Psychiatry, Aboriginal Health, HIV etc.) are advertising an event the type of food being served is promoted equally or more than the presenter or topic.

- For small group learning sessions (6 students + 1 faculty member) we often assign roles including facilitator, note-taker and snack provider. In fact, the role of snack provider was highlighted in the course introduction as essential.

- We used red and blue smarties to learn about gas exchange. Then we get to eat the smarties.

- Our class has a close connection with the wonderful lady who runs the coffee shop in the medical building. We give her birthday gifts, stop to chat and always grab a cup of Joe.

- It’s a great day when the person sitting next to you brings a box of timbits for an early morning lecture. That person always seems to share generously.

- One student in our class bakes cupcakes, truffles or some other delicious snack each and every month for 100 students to celebrate the birthdays

- Food in the hospital could be a whole other topic! Maybe I’ll discuss again clerkship. Funny anecdote for now: We are all enjoying some apples and caramel dip when a nurse comes. One person asks “did you get the dip [referring to the caramel and apples]”. “No I couldn’t get her to pee [referring to her patient that needed a urinalysis]”.

So, what are the implications of all this food that works its way into medical school both formally and informally. I would argue they are huge.

- First off, there may be a few more people in our class who later choose to practice family medicine. It is well known that the Family Med Interest Group has the best food. They don’t do pizza. They bring in Thai food, Greek food, sushi etc. The real deal, every Monday night. Now, I am not saying that people choose family medicine for the food but the food gets them out to the meeting, they like what they hear then think “hey, maybe this is for me”. No joke, food (whether it be interest groups or at rounds) might be impacting students’ career choices. Somebody should study this.

- The idea that food can be an important part of an effective team is working its way into our understanding. Now is this true? I think so. Evolutionarily it is hard to believe that coming from primates we have a desire to share food. But a few reasonable theories exist about why we do so:

- We share food with children so that they can survive [pretty good reason but not applicable to med school].

- We share food with unrelated adults for sex [again not particularly applicable to med school but may substantiate the saying “The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach”]

- We share food with unrelated adults to form and strengthen coalitions [now this makes sense for teams in med school]

- Many of us spend a bunch of time eating alone…grabbing a bite to eat while we are studying, or a quick something on the way home from the gym. Sharing of food at school is something that we don’t do often enough outside of class so we find another way to work it into our lives. This might be evidence that we need to work harder to find time to share food outside of the classroom.

So here are the take home messages- medical students like food, medical students like free food, medical students should spend more time sharing food in a social setting and yes, food likely makes teams more effective. What is your experience with food in medical school or teams?

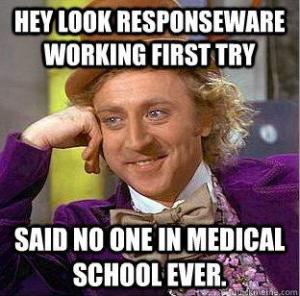

At my medical school we use ResponseWare, one of many audience response systems (ARS), during the preclerkship years to respond to questions during lecture. The general idea of this type of system is that professors can embed questions into presentations that students respond to at specific times when “polling is open”. The answers from the audience are then made immediately available. The technology can be used in different ways. For example, it can allow professors to identify if the crowd understands the concept and address the knowledge gap if one exists or move on quickly if it does not. Or it can also be used a method to generate discussion about a controversial topic (ie poll the class anonymously on a reaction to an ethical scenario then use these results to probe the class). The value of ARS is hard to deny. Studies suggest that, when used correctly, an ARS makes classroom lectures more engaging and interactive with positive learning outcomes. Even in the specific context of medical education ARS seem to be a promising tool.

The catch is, IT HAS TO WORK to be of any value. This meme crossed our lecture hall during our professor’s 15 minute battle with Responseware, which was certainly hard fought but eventually lost.

My issues with ResponseWare have nothing to do with the educational concept but with the system itself. Let me break down the problem:

- Students have to pay $50 for 4 years of use when there are free alternatives (i.e. mQlicker, twitter)

- 100 students paying $50 = $5000… we have successfully used the technology 5 times. Quick math makes that $1000 a ResponsWare session. Yikes!

- Our professors work really hard on lectures for us- I feel bad when they get to the front and they can’t get the system to work.

- The tech rep, a med student with profound techonological capabilites, is a smart dude- I feel bad when he can’t get the system to work.

- The tech guy working for the medical school, who can figure out every other piece of high tech equipment and solve all other problems for the technology challenged, is a smart dude- I feel bad when he can’t get the system to work

- Instead of using a program to spend 15 minutes exploring important medical concepts, 3 smart dudes fight with ResponseWare- I feel bad when they inevitably give up and decide to use the traditional show of hands method

- While these 3 feel bad about being defeated by ResponseWare the rest of the class feels bad about making fun of their efforts through the production of memes.

- At the end of the day everybody has less money in their pocket, everyone feels bad and we are running 15 minutes behind schedule.

So what would the ideal ARS look like for me? One that is easy to use (for professors and students), one that is cheap (preferably free) and one that enhances (or at least doesn’t impede) the learning experience. Do you have any suggestions?